Taking The Real Birth Company to Med-Tech Malta

2 November 2023

Midwife Zoe Wright Hosts Successful Birth Choices Awareness Workshop

5 December 2023

Reviewing the OASI Bundle

In 2020 Emma Ashworth and Zoe Wright wrote an article called ‘Tearing through the evidence – The OASI Bundle’. With the recent announcement that from April 2024, NHS England will implement new Perinatal Pelvic Health Services (PPHS), there may be some significant changes seen across the UK. But what about OASI? What has improved, and how has this very hands-on intervention become normal practice? Sarah Smith and Zoe Wright review the evidence to see what has changed in 3 years.

New pelvic health services to be rolled out next year

At the end of last year, the Government announced its plans to roll out new nationwide Perinatal Pelvic Health Services by March 2024, in line with the NHS Long Term Plan’s commitment to improve the prevention, identification and treatment of poor pelvic health and pelvic floor dysfunction. The Government has committed to invest £11 million into the new service by April 2024.

The idea is that by 2024 everyone will have access to specialist pelvic health services antenatally, and for at least 12 months postnatally. The service will incorporate a multi-disciplinary approach pooling expertise from specialist midwives, pelvic health physios, doctors, and mental health specialists, ‘to ensure that all pregnant women receive advice and support to prevent pelvic health problems, and that those with problems are offered conservative treatment options before surgery is considered, in line with NICE Guidance’.

Pelvic health has long been an underrepresented area of care within women’s health, which is now finally getting the attention that it deserves. This is a much-needed step in the right direction.

What do we mean by pelvic health?

We use the term ‘pelvic health’ to refer to the muscles and structures that support the pelvic floor and the pelvic organs – the bladder, vagina, uterus, and the rectum. Damage to, or weakening of the pelvic floor can lead to ongoing problems or poor functioning of these organs throughout life.

Maintaining optimal pelvic health plays an important role in complete physical, mental, social, and sexual wellbeing. It is essential for quality of life and the prevention of both short and long term issues.

So it’s important that we understand what to look out for, when to be concerned and where specialist support and health services can be accessed if required.

A hidden problem

It is estimated that 1 in 3 women experience urinary incontinence 3 months after pregnancy, 1 in 7 people experience anal incontinence 2 months after birth, and that 1 in 12 women report symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse.

These figures are high, but what’s more concerning is that these figures are likely to be much higher in reality, as many women do not seek support for pelvic health problems due to either being too embarrassed or ashamed, or a belief that problems are normal or to be expected after having a baby, and therefore they just put up with them.

Many are also not aware of services which are available to them to help them with these concerns. Many people are suffering in silence unnecessarily with problems that in many cases can be reversed or at least improved with the appropriate treatment.

Pelvic floor disorders can have a devastating impact on women’s lives – not just in the initial perinatal period after birth, but if left untreated can cause lifelong problems affecting an individual’s ability to work or exercise, their social life, sexual health, future reproductive health and mental wellbeing.

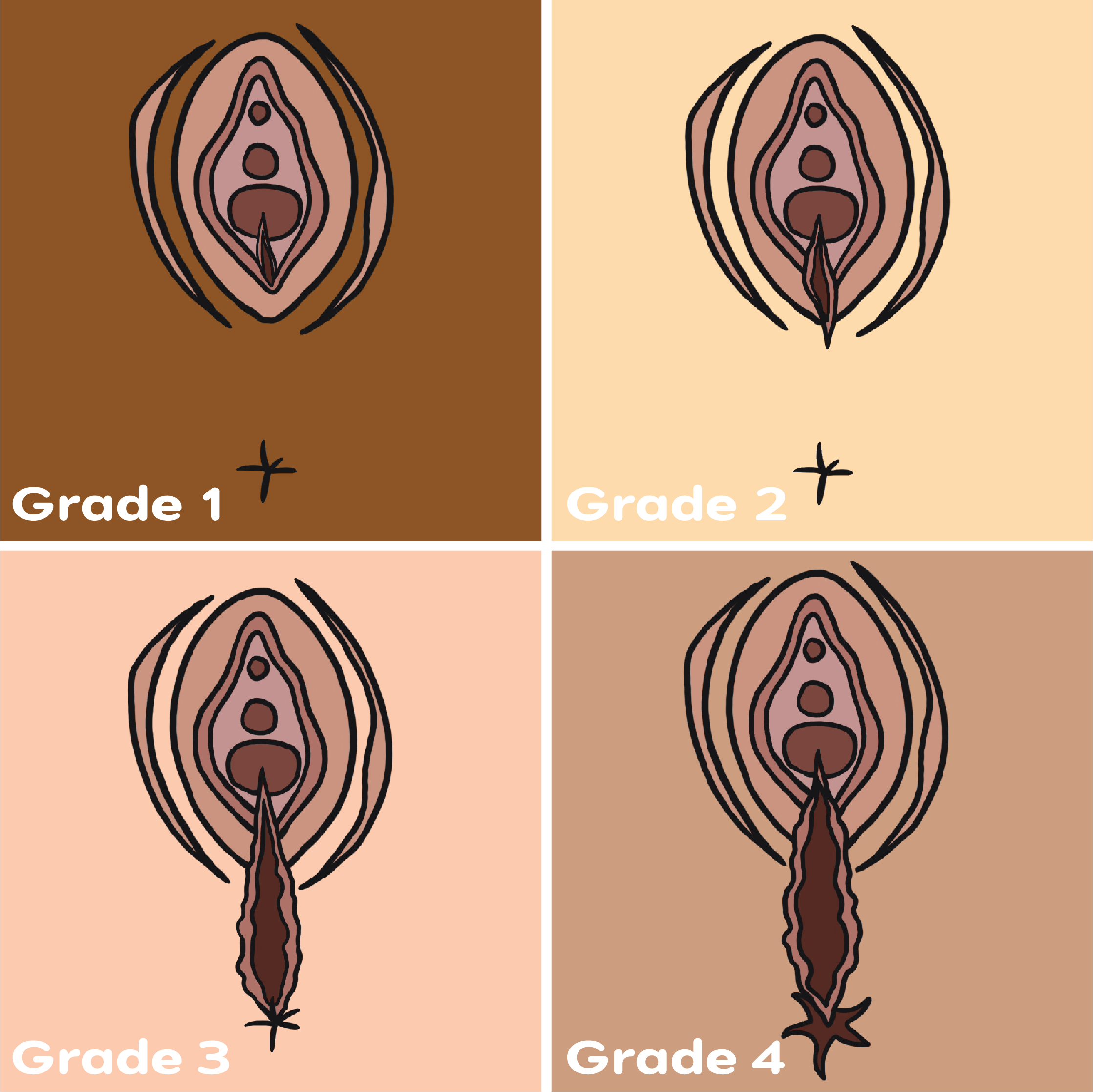

Birth Injuries

According to Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) up to 9 out of 10 women giving birth to their first baby vaginally will experience some sort of graze, tear, or an episiotomy. These types of birth injuries will range in severity from relatively minor superficial tears to more significant severe injuries. The more significant injuries involve the muscles and tissues of the anus, and are often referred to as third or fourth degree tears, and collectively as obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASI) or Severe Perineal Trauma (SPT). Third and fourth degree tears require accurate identification, specialist repair and post birth support and rehabilitation often requiring follow up appointments and physiotherapy.

For further classification on of perineal tears, click here for more information.

Thankfully, severe perineal trauma is less common. Third or fourth-degree tears, can occur in 6 out of 100 births (6%) for first time mothers and less than 2 in 100 births (2%) for women who have had a vaginal birth before (RCOG).

What is the OASI care bundle?

The preventative actions related to reducing perineal injury as referred to above, are the implementation of the OASI care bundle, which was developed in an attempt to reduce incidences of SPT in birth. It was supported by an awareness campaign and multidisciplinary skills development. OASI2 is a Spreading Improvement project that will further investigate the mechanisms and strategies that support the sustainability and spread of the OASI Care Bundle, with the primary focus shifting from clinical to implementation effectiveness.

Care bundles are designed to group evidence-based practices together in order to reduce variation in health care practice and outcome.

The OASI care bundle was initially piloted between January 2017 and March 2018 in the UK, in 16 separate maternity units, and was then rolled out to further units in 2019 driven by 2 political bodies the RCOG and the Royal College of Midwives (RCM).

The OASI care bundle includes 4 components:

- Antenatal information about OASI and what can be done to reduce OASI during birth

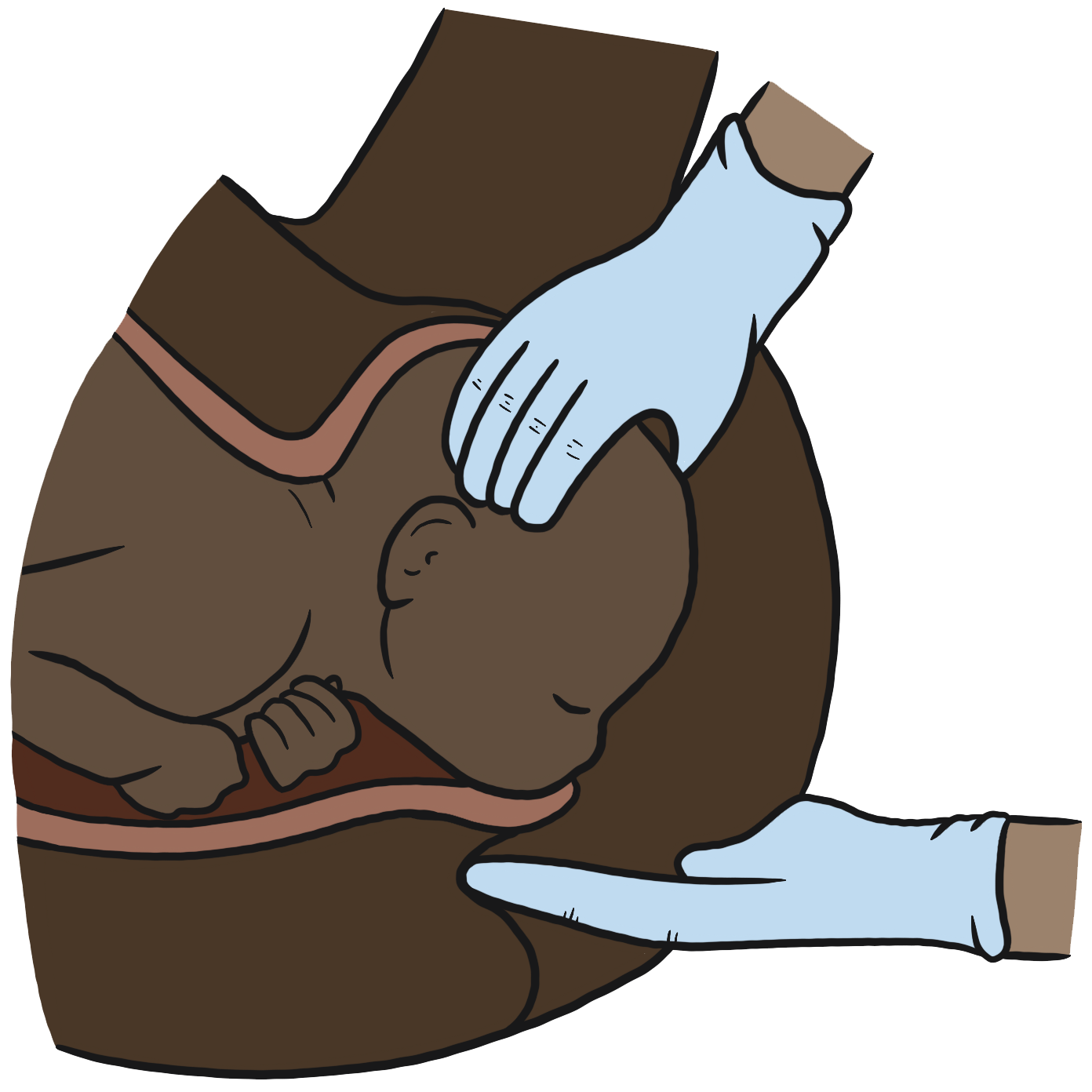

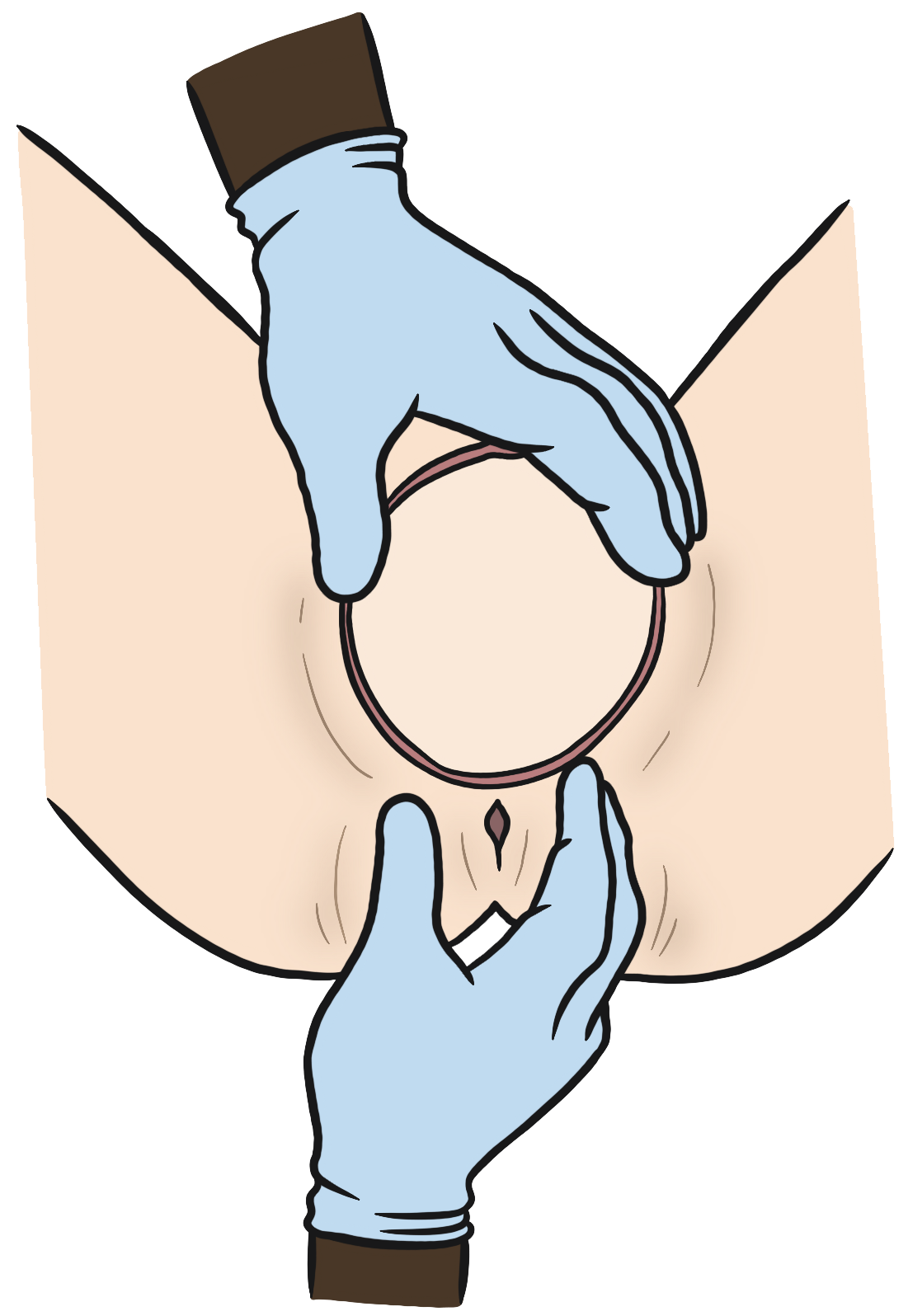

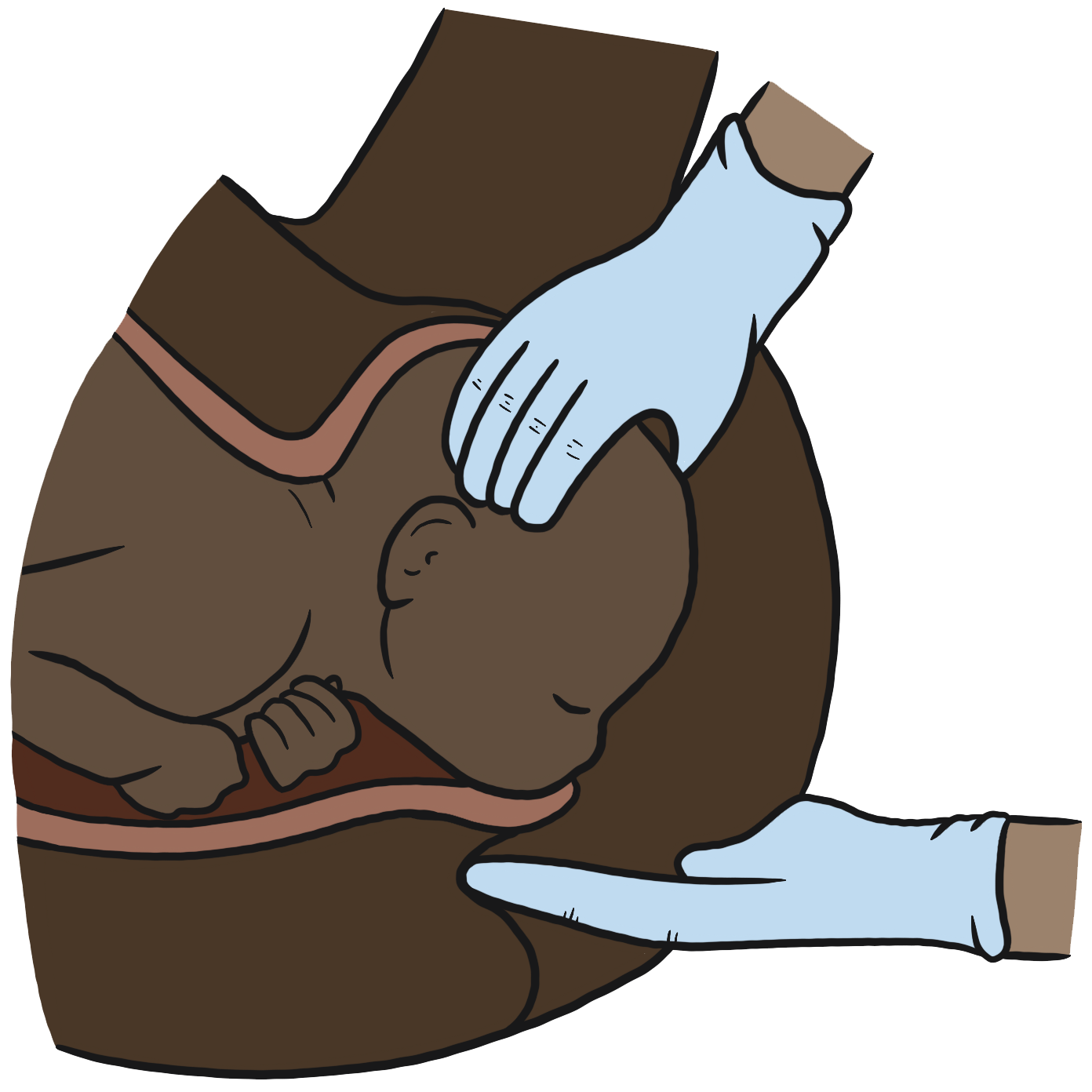

- Manual Perineal Protection (MPP) for all vaginal births – applying pressure to the baby’s head and the perineum during birth (‘unless the woman objects’ or ‘chosen birth position doesn’t allow for it’) whilst communicating and encouraging a slow guided birth

- An episiotomy (if clinically indicated) performed at a 60-degree angle (a change from current normal practice) from the midline at crowning

- A vaginal and rectal examination for all women following the birth (even when the perineum appears intact).

The pilot study enrolled over 55,000 women who had vaginal births and reported a reduction in OASI injury from 3.3% to 3.0%.

Let’s first start by emphasising that any reduction in the rate of SPT injuries is positive. There is no doubt that injuries such as these, are profound and can be devastating – both physically and emotionally, for those who experience them, and that we should be doing everything in our power to try and minimise their occurrence – there is no disputing that! Women who have sustained a third or fourth degree tear are at higher risk of anal incontinence in later life, sexual dysfunction, and have a 20 times higher risk of a caesarean section in subsequent pregnancies.

However, these figures aren’t exactly outstanding. The OASI data reported reducing incidence of severe perineal injury by 0.3%. This means that prior to the bundle being implemented, the rate of OASI was 33 per 1000 women, and following rates reduced to 30 per 1000 women.

Not only are these results not earth shattering, but a recent review has highlighted concerns in the evidence upon which it’s based, the research findings, and fears it may be ineffective in the long run and possible unintended harms that may exist as a result of the OASI bundle being used in practice.

Let’s dive a little deeper.

The research

The OASI bundle came about following the RCOG’s response to an apparent tripling of the rate of third and fourth degree tears from 1.8% in 2000 to 5.9% in 2011. It’s important to note that many of the authors of that study are the same authors of the OASI trial. In the 2020 review, the authors themselves acknowledged that the most likely ‘cause’ of the supposed tripling of the OASI rate, was most likely due to ‘improved recognition’.

Meaning that the RCOG’s need to act, may have been founded on an inaccurate reflection of the data. Rates of STP may not have actually tripled, but that they were simply being identified more frequently.

Not only this, the evidence on which the OASI Bundle is based has been questioned, as many elements of the bundle are not supported by robust evidence.

Let’s take a look at the individual elements of the bundle below.

Antenatal information

When planning a birth, everyone needs to understand the risks and implications of SPT and ways in which rates can be reduced, but this conversation needs to go far beyond simply explaining and recommending the OASI care bundle. Providing one-sided information does not give people the ability to make informed evidence-based decisions about their care. The information that was provided to women about the care bundle did not mention any possible alternative methods to reduce SPT. There were issues regarding gaining true informed consent, without which, nobody should be performing any other aspects of the OASI bundle during childbirth.

Manual Perineal Protection (MPP)

This topic has sparked discussion amongst birth professionals for many years. The topic is controversial as there still remains no clear evidence to support either a ‘hands on’ or a ‘hands off’ (poised) approach to birth. A Cochrane review on perineal management supports neither a hands poised or a hands on approach, and therefore a ‘best practice’ approach has not been determined. Therefore, to impose a prescriptive, invasive hands-on approach for all births (regardless of perceived risk) as part of the OASI bundle as a blanket rule, surely goes against our midwifery professional standards – ‘to optimise normal physiological processes’ (RCM).

The OASI guidance is contradictory, as it also states that MMP should not ‘replace reasonable clinical judgement’ which should include a judgement of who is most at risk and individual circumstances.

A recent Australian study showed no difference in SPT in people having their first baby and an increase in SPT in women having a subsequent birth when a hands on/directed pushing approach was used, compared to the hands poised/undirected pushing approach <span "="">(Lee et al 2018).

The information given to women antenatally does not adequately describe MPP ‘manually supporting both your perineum and the baby’s head as s/he is born’ – is not a true reflection of what is meant by the ‘Finnish Grip’ it refers to on the care bundle website. It’s thought the Finnish Grip increases the likelihood of tears being diverted away from the anal sphincter and towards the front. However, there is concern that this practice may increase anterior and clitoral tears.

Episiotomy (if clinically indicated)

An episiotomy performed at a 60-degree angle (instead of a 45-degree angle) also lacks a solid evidence base. There have been two small randomised trials testing this change in practice, and neither reported a significant reduction in SPT rates with a 60-degree angle (El-Din et al 2014, Chikkagowdra 2022). Studies analysing the use of specially designed episiotomy scissors (Episcissors-60) which were designed to achieve an accurate 60-degree episiotomy from the midline, demonstrated no change in SPT rate (Ayuk et al., 2019).

When an episiotomy is performed at a 60-degree angle there is a disregard for our anatomy and physiology as it extends into the structure of the clitoral body and the clitoral nerves which surround it. We have only recently begun to understand the full complexity of the clitoris in its entirety, and even now, this current knowledge is not reflected in most textbooks.

Episiotomies in general, are associated with decreased sexual functioning, desire, arousal, and orgasm within the postpartum five years ( Dogan et al 2017). We also know that episiotomies are associated with greater postnatal pain, increased anal incontinence (Garner et al 2021), and do not heal as well compared to spontaneous tears. These factors should not be taken lightly – we need to ensure we avoid episiotomies unless truly clinically necessary.

The OASI guidance specifies an episiotomy should be performed for ‘all term forceps and ventouse/kiwi births in nulliparous women. In multiparous women, an episiotomy should also be used for all term forceps birth, but may occasionally be omitted with a ventouse birth’. This recommendation will increase the incidence of episiotomy as sometimes experienced skilled doctors are able to facilitate a ventouse or kiwi birth without the need for an episiotomy.

Mandating that all assisted births for women having their first baby, and only ‘occasionally’ omitting them for multiparous women having a ventouse birth, eliminates the use of clinical judgement on the part of each individual doctor.

Thornton & Dahlen (2020) have argued that the implementation of the OASI bundle has increased rates of episiotomy, which in itself is a risk factor for SPT – the very thing the bundle is aiming to reduce. When comparing other perineal protection bundles the use of episiotomy has also been noted to increase significantly (Jango et al 2019).

Vaginal rectal examination

This element of the bundle has been highly criticised. A vaginal and rectal examination is standard practice where an episiotomy has been performed or second (or 3rd or 4th) degree tear has been identified. It’s important to accurately establish the extent of a tear so it can be sutured appropriately. However, a routine rectal examination for everyone who gave birth to rule out anal sphincter damage or ‘buttonholing’ in the presence of an intact perineum is the part that is being criticised. The rationale behind this element is to identify ‘hidden’ third and fourth degree tears which might otherwise be missed. However, it is unknown whether a digital rectal examination in the presence of an intact perineum can even detect this type of injury, and even if it could, there is no established protocol or treatment to address such an injury. There’s little evidence of any statistics documenting the occurrence of third and fourth degree tears with an intact vaginal wall and perineum, therefore subjecting everyone to this undignified procedure is questionable.

Additional research & alternatives

A very similar perineal protection bundle developed by Women’s Healthcare Australasia (WHA) was implemented in 28 Australian maternity hospitals in 2018. Their website claims the bundle reduces incidence of SPT but findings have not yet been published. The Australian bundle consisted of 5 elements with the main difference between the UK OASI bundle and this one was the addition of warm compresses at birth.

Independent research by Lee et al (2023) attempted to answer the question as to whether the WHA care bundle did in fact reduce the incidence of SPT. This is what their data concluded:

- SPT rates in 2012 – 4.1%

- SPT rates in 2017 – 1.9% (already declining prior to the implementation of the bundle)

- SPT rates in 2019 – 1.9% (after implementation of the bundle)

- SPT rates in 2020 varied from 2.9% in unassisted to 6.8% in assisted births

- Episiotomy rates steadily increased over time from 4.8% in 2012, 8.5% post-bundle, to 11.5% in 2020

- Two years after implementation of the WHA bundle SPT rates were higher than the period prior to implementation.

- The bundle increased rates of episiotomy for some, and increased rates of second-degree tears in others.

Warm compresses & perineal massage

A randomised controlled trial on the use of warm compresses on the perineum, concluded this simple and inexpensive intervention increased the rate of intact perineums, lowered the rate of both third and fourth degree tears and episiotomy. It has also been found to be highly acceptable to women and midwives (Dahlen et al 2009, Dahlen et al 2007, Aasheim et al 2017). The use of warm compresses to reduce SPT is the only intervention supported by high quality evidence. It’s concerning therefore that this was not included as one of the elements within the OASI bundle. However, the researchers behind the OASI care bundle have defended this omission by stating that whilst they agree there is evidence to support warm compresses, it was not included within the bundle because many units were unable to ensure heat packs could be warmed adequately, but encouraged that if it’s part of a clinician’s current practice, then they should continue. However, this seems questionable as every unit will have access to warm water, otherwise it poses an infection control risk. The use of warm compresses has now been added to the new OASI2 version of the antenatal information to discuss with birthing people, although is still not one of the components within the actual care bundle.

Similarly, perineal massage to reduce SPT was not included in either the WHA or OASI care bundle despite there being high level evidence to support this practice (Abdelhakim et al 2020). Beckmann et al 2013 also concluded that perineal massage decreased the likelihood of needing an episiotomy. Perineal massage also facilitates a sense of control over their own body, rather than the reliance of interventions which are done to them by clinicians.

The Physiology

The Real Birth Programme continues to teach a deeper understanding of the changes that take place to the perineum as birth progresses.

The perineum is a highly complex and perfectly designed group of muscles, tissues and nerve endings that thin out and stretch to assist with the birth of the baby. The relaxing of the muscles, the lengthening of the fibres and movement of the tissues are supported by the hormones released in pregnancy including relaxin and progesterone. As the baby’s head or bottom is moves down the birth canal, consistent pressure on the rectum creates a hormonal feedback response that further relaxes the muscles of the perineum, and supports the thinning and stretching of the fibres.

At the same time, the muscles of the perineum produce a counter pressure on the baby’s presenting part. In most births this is their occiput. This counter pressure supports the moulding of the head, ensuringthat the baby’s head reduces to the smallest diameter, enabling it to proceed through the birth canal with ease.

A change in pressure caused by moulding of baby’s head, reduces blood flow passing through the baroreceptors. This is a normal response which supports their stables oxygen levels in the baby.

Oxygen saturation levels in the fetus are approximately 80%, compared to 98% in the adult circulation. In response to these lowered oxygenation levels, the baby lowers its heart rate.

Throughout this phase of birth, continuous pressure and hormonal influences helps to keep the muscles of the perineum soft. The muscles continue to be supplied with a strong blood flow during the periods of rest in between pushes. The positive pressure helps the fibres to releases, relax and stretch.

Pressure from the fundus of the uterus during a tightening passes through the baby’s pole and gently supports the movement of these muscles.

This process happens more quickly and with less trauma, the greater the blood flow is through these muscles and tissues. The flowing blood acts as a ‘cushion’.

We believe through research, informed practice, and evidence-based information, that directed pushing, lying on your back and having your legs placed wide open for birth, causes this natural feedback loop to be broken.

Directed pushing, which involves breath holding and a forced and sustained pushing technique, reduces oxygen and blood flow in the tissues, and creates additional resistance within these muscles.

Resistance comes from forcing the presenting part onto muscles which are not yet ready to stretch. The additional sustained pressure from directed pushing depletes the blood flow for longer than would naturally occur during spontaneous pushing efforts. This increases the resistance in the muscles, making the muscle fibres less flexible and more at risk of tearing. The reduced blood flow also reduces the levels of hormones that are there to assist with the flexibility and growth of the perineum.

If we look at athletes, it’s well understood that muscles need to be warmed up prior to exercise, and that cold muscles are easier to cramp, tear or become damaged if they’re not looked after properly. Asking someone to push as hard as they can when the muscles are not ready will cause damage, and the above situation is likely to occur.

In addition, let’s now consider birthing in a semi-reclined position or on our back.

Having your legs placed in a wide open position puts additional pressure on the perineum. This additional pressure, occurring simultaneously with a counter pressure in the opposite direction from the uterus through the baby’s pole, puts more pressure on the baby’s head than is biologically ‘normal’.

Greater pressure on the baby’s head through directed pushing, leads to higher pressure on baroreceptors within the already moulding head. This creates greater changes in the heart rate as the baby tries to conserve oxygen by slowing the heart rate further, leading to the birth attendants asking the birthing person to push harder. It has been noted in many studies and trials, that practices similar to those contained in the OASI care bundle see increased rates of episiotomies.

Frequently, women unintentionally birth their babies quickly, still wearing tights, leggings, pants, and trousers, without their legs wide open, and very rarely sustain tears. The natural instinct to close our legs during this specific part of birth, is there to help reduce pressure and protect the perineum.