The Role of Individual Health Needs in Shaping Birth Plans

12 December 2024

Fasting During Pregnancy: Guidance for Expecting Mothers in Ramadan

26 February 2025A review of standardised newborn tests by Sheffield Hallam University commissioned by the NHS Race and Health Observatory (RHO), has highlighted how outdated assessment tools used to assess a baby’s condition after birth, are ineffective, unreliable and ‘not fit for purpose’ for many babies from global majority backgrounds. Ineffective practices are therefore amplifying racial biases, inequalities and aiding the process of further widening the health disparity gap in maternal and neonatal healthcare.

Health Disparities in Maternal and Neonatal Care

It's well documented and evidenced that significant health inequalities are apparent in the UK across our maternal and neonatal health systems and care provision. It’s now over 6 years since the MBBRACE-UK 2018 report was published, which first highlighted ‘glaring and persistent disparities’ for birthing people and babies depending on their ethnicity, and still, little improvement in health outcomes for mothers and babies from global majority groups has been made.

The Evidence

As it stands, black women in the UK are 4 times more likely to die in childbirth and in the first postnatal year, compared to their white counterparts. Asian women are nearly twice (1.8x) as likely, and mixed ethnicity women are 1.3 times more likely to die, compared to white women. According to data from the latest National Child Morbidity Database (NCMD), black babies are now dying at 3 times the rate of white babies in the UK, as rates have increased alarmingly since 2020. Statistics from NCMD show that death rates for white infants have remained steady at around 3 per 1,000 live births since 2020, but the rate for black infants has risen sharply from just under 6, to just over 9 per 1,000 live births within the same time frame. To put these figures into context, in the year up to April 2024, 50 more black babies died compared to in the previous year. In addition, infant mortality rates in the poorest neighbourhoods also rose to double those in the most affluent areas.

With the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbating strains on health services and increasing mortality rates now at their highest since the database began in 2019, urgent action is now needed.

This has prompted further analysis and a review of current neonatal assessment, practice, and guidelines for assessing a baby’s condition after birth. These were put under the spotlight to determine whether standardised tests were appropriate and reliable for global majority babies. Until recently, very little work had been done to understand if current guidance surrounding these assessments were suitable for black, Asian and mixed ethnicity babies and those with darker skin tones.

The Problem

The NHS RHO ‘Review of Neonatal Assessment and Practice in Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic Newborns’ (July 2023), predominantly focused on 3 main areas of concern; practices including the Apgar score, and assessment of cyanosis and jaundice - all of which involve a visual assessment of a baby’s skin tone or colour (pigmentation) to assess wellbeing. This followed concerns that these procedures were historically based upon guidance from the 1950’s (Apgar score) which was developed based on white European babies and has been normalised regardless of their applicability to diverse populations and babies with varying skin tones (Kapadia et al., 2022).

The report aimed to examine whether the use of certain terminology used within these assessments was appropriate for practice and assessment of non-white babies, and to make recommendations for practice as needed.

It also involved a systematic review of literature on the experiences of parents or carers when accessing healthcare, as well as interviews with healthcare professionals to identify challenges and barriers to accessing or receiving care, areas of good practice and any instances of discrimination or inequalities within care.

The APGAR Score

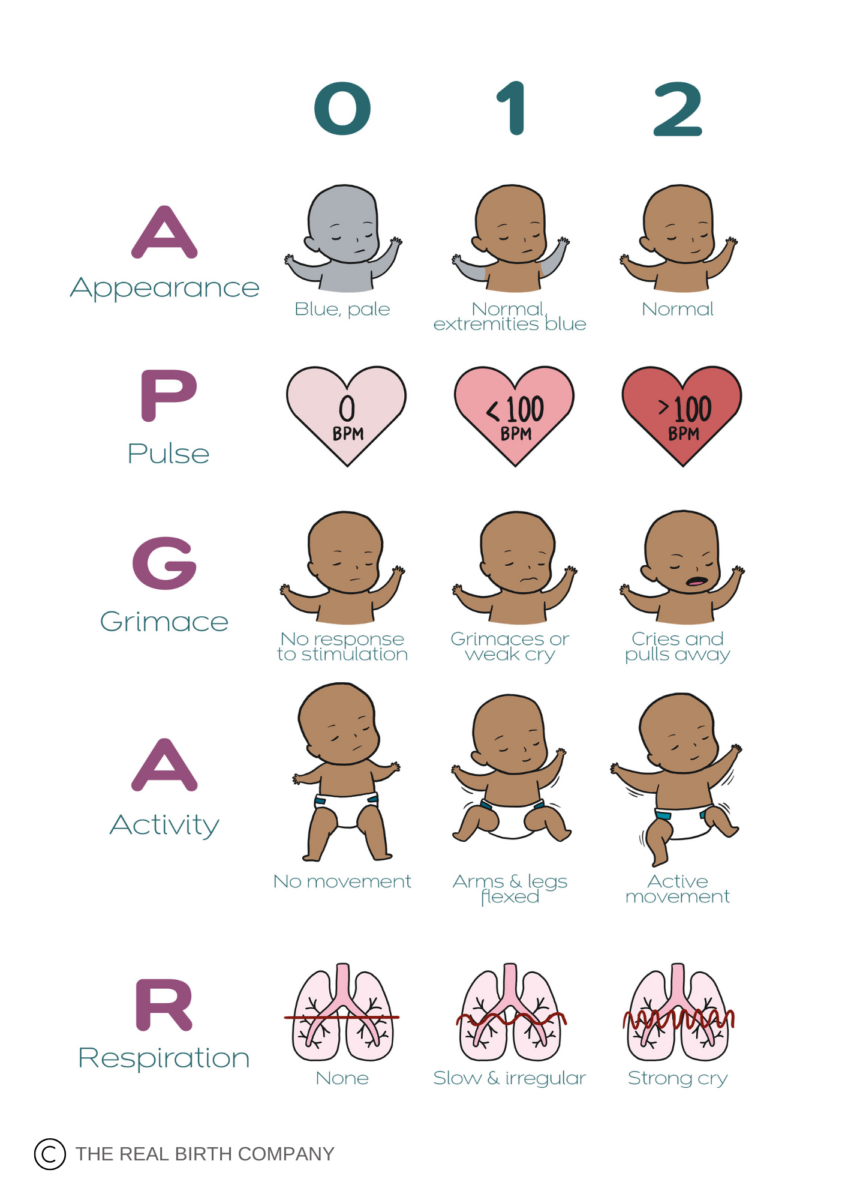

The Apgar score is a standardised method of assessment performed on all newborns at birth. It’s designed to quickly assess a baby’s wellbeing at birth by focusing on 5 areas.

A - Appearance (skin colour)

P - Pulse (Heart rate)

G - Grimace reflex

A - Activity (muscle tone)

R - Respirations (breathing effort)

The assessment is performed at 1 minute and at 5 minutes following birth and aims to quickly identify those babies who need further medical care and support, to improve survival rates. The test can be performed at further 5

minute intervals for those babies who need additional ongoing medical attention.

Each of the 5 areas is given a score from 0-2 depending on how the baby is responding. Those scores are then tallied up to give a score out of 10, at the 1 and 5 minute intervals.

The Apgar score is named after American physician, obstetric anesthesiologist, and medical researcher Dr. Virginia Apgar (1909-1974).

The Apgar scoring system was designed in 1952 after she began to realise that little attention was paid to infants and their physical condition after birth.

Cyanosis

Cyanosis occurs when the body is not receiving enough oxygen in the blood, or when there is poor circulation.

In newborn babies this can be an indicator of a serious problem with either the heart, lungs or the airway, and the ability to pump blood (oxygen) effectively around the body.

This condition is detected by noting a change in colour of the skin or mucosa, typically the skin, lips, tongue or gums.

This is often characterised by a ‘blue’, ‘purple’, ‘grey’, or ‘pale’ appearance of the skin or mucosa.

Babies may appear limp and floppy due to low oxygen levels, and if left untreated can deprive the brain of oxygen resulting in potentially life long injury. Therefore early detection and treatment is key.

Jaundice

Jaundice is a condition caused by a buildup of bilirubin, a substance with a yellow pigment, which occurs as the body breaks down old red blood cells.

There are different types of jaundice. Physiological jaundice is transient that occurs due to the normal transitions that babies go through as they adapt from life in the womb, as they break down red blood cells no longer needed. Physiological jaundice usually appears around day 2-3 postnatal.

Pathological jaundice is a type of jaundice that some babies can develop in the first 24 hours of life, or if the bilirubin level is very high in the first 10 days of life. This type of jaundice is often caused by a disease or condition, and is more serious.

Breast milk jaundice, is common in babies who are breastfeeding, and usually appears around day 5-7, typically peaking around 14 days postnatal. It’s thought to be caused by a buildup of an enzyme found in breastmilk, and is normal.

Jaundice is characterised by a ‘yellowing’ of the skin of the whites of the eyes.

High levels of bilirubin if untreated can cause seizures, learning disabilities and hearing problems. Therefore early detection and treatment, if necessary, is key.

The Report

The report highlighted concerns regarding clinical accuracy, and that the Apgar assessment (particularly the ‘appearance’ component) may give misleading scores for global majority babies. Visual checks for jaundice (involving assessment of the skin and the sclera of the eyes), and assessment of cyanosis also involving visual assessment of skin colour, were frequently inaccurate, leading to ‘reliability concerns’, resulting in potential late or missed diagnosis and poor health outcomes for these babies.

One study from the literature analysed, considered healthcare professionals’ training. Midwives and student midwives reported a lack of education in clinical assessment of black, Asian, and global majority mothers and babies, with the study particularly focusing on assessment of the Apgar score. After the training, 96% of midwives felt the Apgar score was not the most appropriate way to assess all babies at birth due to the description of colour within it. In another study, maternity care assistants’ knowledge and self-perceived confidence in detecting jaundice was not associated with actual ability to correctly estimate SBR (serum bilirubin) levels from visual assessment. The majority of healthcare professionals within this study stated that they had received no additional training in identifying jaundice, cyanosis, or undertaking an Apgar score in black and global majority neonates.

“The results from this initial review highlight the bias that can be inherent in healthcare interventions and assessments and lead to inaccurate assessments, late diagnosis and poorer outcomes for diverse communities.”

The report concluded that assessments focusing on visual inspection alone due to their subjective and problematic nature, were unreliable, and could lead to false positives and false negatives, especially for those babies with darker skin. This has the potential to disadvantage global majority babies. It recommended that in practice if there is any doubt or concern regarding a baby’s breathing, oxygen levels or potential jaundice, that more objective measures are taken rather than relying on visual inspection alone. This includes the use of pulse oximeters, bilirubinometers or blood tests - all of which are better designed, and give more consistent results for global majority babies, or those with darker skin. The report highlighted the suitability of the Apgar score to be urgently reviewed, and called for better training for healthcare professionals carrying out assessments on newborns, particularly those from global majority backgrounds.

Professor Jacqueline Dunkley Bent, England’s first Chief Midwifery Officer, has added, “The Apgar score is still a valid tool, but it does not give guidance if the baby is black, brown, or of mixed ethnicity”.

Biased assessments exemplified by terms such as ‘pink’ or ‘pinking up’, were deemed to disregard the diversity of skin colours within our population and without detailing how these skin colour descriptors may vary or present in global majority babies. Language and practices that are based on a white-normative standard further perpetuate the inequalities already faced by those from an global majority group.

Despite years of awareness of the inaccuracies of visual assessment as means of assessing a baby’s wellbeing, particularly babies from global majority groups, this has not been translated into policy changes, updated guidance, or comprehensive healthcare education.

“It has been known for decades that certain medical practices are not fit for purpose and directly discriminate against those with darker skin tones and yet, there has been no action to address this in any concerted way.”

here is a distinct lack of training and learning resources which educate on how certain conditions may present in individuals with varying skin tones. This has been an issue detected more widely in medical literature in recent years.

In 2021, Nigerian medical student Chidiebere Ibe received praise and recognition after publishing a medical illustration drawn by himself, depicting a black fetus in a black woman’s womb which went viral. The post was retweeted 50,000 times and gained 88,000 ‘likes’ on Instagram. Ibe began publishing medical illustrations and images featuring black bodies as a deliberate act to advocate for the inclusion of black people and equality in medical literature, and to address how certain conditions may present on individuals with different skin tones.

“Little did I understand what the drawing meant to a lot of people … People could see themselves in the drawings…”

Just 4.5% of images in general medicine textbooks show dark skin. According to Ni-ka Ford, Chair of the Association of Medical Illustrators (AMI), this is an “extension of medical racism”. Accurate learning resources are imperative for accurate and timely diagnosis, and essential to improve patient care and outcomes.

During the creation of our new preterm birth module last year, we tried to address some of these issues by creating a new visual depiction of the traditional Apgar score table, and an accompanying video to try to help parents better understand what the Apgar score was all about. When addressing the ‘Appearance’ element of the score, we were aware we needed to go beyond the standard ‘blue’ and ‘pink’ descriptors that are traditionally used - so took the opportunity to do so within the video we created. In the video we explain that the ‘colour’ or ‘tone’ of the baby’s skin is not related to their ethnicity, but related to the perfusion (oxygenation) of the body.

Summary of Report Findings

UK guidelines, policy and training regarding neonatal assessment, do not adequately address differences in skin pigmentation, but frequently rely on the assessment of a newborn’s skin colour as a predictor of wellness. The implication is that assumptions made regarding skin colour assessment, may only be relevant to those with white skin, and not inclusive or representative of those with differing skin tones and those from global majority groups. Given that visual assessment by a healthcare professional remains the first line of screening before further tests or treatment are accessed, this may disadvantage ethnic global majority babies.

Key Themes Emerged Included:

- Communication barriers - including language differences or inadequate translations

- Feeling silenced, unheard, dismissed, ignored, belittled

- Fear of raising concerns or being labelled as ‘difficult’ to ‘too much trouble’

- Discrimination in healthcare - including stereotypes, lack of cultural competence, inadequate care, unfounded racial assumptions and racist microaggressions

- System and organisation factors - including difficulties around accessing appointments and care, lack of flexibility, staffing issues and workload pressures

- Lack of training and awareness making biases and discrimination more likely

- Charging for care to some migrants depending on status was also seen as an organisational barrier

- Social isolation, socio-economic status, and racism in society were identified as contextual issues impacting maternity care.

“This highlights the need for HCPs [healthcare professionals] to be more culturally competent and provide personalised culturally safe care, as well as the need for more support for parents from seldom-heard communities. Addressing discrimination in healthcare, society, and decolonising the curriculum, practice and policy is crucial for improving maternal and neonatal health outcomes, ensuring that all parents receive respectful and dignified care”. ~ NHS RHO report.

Racial discrimination is unlawful. The Equality Act 2010 states people must not be discriminated against for their race, colour, nationality, ethnic origin and ethnic or racial group (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2020).

“From the moment a child is born, the healthcare that black and minority ethnic babies are afforded is designed and delivered based on white European measures that are inadequate and inappropriate to their care.” “Until we take seriously an anti-racist approach to healthcare, black and minority ethnic people are being actively harmed.”

All children have a right to the best possible chance at life, regardless of their ethnicity or background. Closing the gap in infant mortality rates must become a national priority.

Learning Points

- Highlighted existing inequalities in neonatal outcomes

- Urgent need for more objective measures of assessment

- Tests to assess newborn health deemed ineffective for non-white infants

- Outdated terminology e.g. ‘pink’, ‘pinking up’, ‘blue’, ‘pale’, ‘pallor’, and ‘yellow’ deemed unhelpful

- Lack of inclusive teaching resources which frequently do not adequately represent the diversity of global majority communities

- An urgent call for action for transformative change.

Practice Recommendations

- Improved access to use of bilirubinometers and pulse oximeters

- NHS England to create a national data bank of open access images of black, Asian and global majority neonates to incorporate into training and education, and to aid diagnosis in practice

- An urgent need for regular education and training for healthcare professionals and students, and better education for families and general public is also required

- Guidelines that refer to neonatal assessment by skin colour should be immediately reviewed and updated to highlight the impact of race and ethnicity